Research Article - (2024) Volume 19, Issue 1

Stress And Burnout For Parents Of Children With Special Needs A Review From Resilience And Social Support

Cempaka Putrie Dimala*, Puspa Rahayu Utami Rahman, Irwan Tourniawan and Regi Ramadan*Correspondence: Cempaka Putrie Dimala, Buana Perjuangan University Karawang Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, Indonesia, Email:

Received: 15-Feb-2024 Published: 21-Feb-2024

Abstract

Parents of children with special needs experience higher levels of stress and depression than other parents, and problems arise in the family unit. The pressure experienced by parents with children with special needs can also trigger parental burnout. This research was conducted to determine the factors that influence parenting stress and parental burnout in parents with children with special needs, viewed through resilience and social support which act as moderators. This study used a sampling technique, namely purposive sampling, with a total of 334 participants from parents with special needs in Karawang. The measuring instrument used for parental burnout is the Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA) short version, parental stress is the Parental Stress Scale (PSS), resilience is the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD- RISC) and social support is the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). Based on the results of the model test, it is known that the analysis of factors related to stress and burnout in parenting in parents with children with special needs: in terms of resilience and social support matches the empirical data. Based on the results of statistical tests, parental stress has a positive and significant effect on parental burnout, resilience has a negative and significant effect on parental burnout. Meanwhile, social support does not affect parental burnout. Moderation analysis shows that individuals who get social support can reduce the potential for burnout associated with high levels of daily stress due to caring for children with special needs. However, on the other hand, resilience cannot act as a buffer against the development of increased burnout in parents of children with special needs due to parenting stress. Participation and involvement in the social environment can reinforce to hinder the burnout felt by parents of children with special needs

Keywords

Parental stress, Parental burnout, Resilience, Social support, Parents, Children with Special Needs

Introduction

The role and fulfillment of children's rights in care is the responsibility of parents, both mother and father. Parents are mentors, educators, guardians, developers, and supervisors. Becoming a parent is a great potential in an individual's personal development, a transfer of responsibility to a greater one, and a stage to face various challenges. For some, becoming a parent is a difficult journey that involves worrying about their child, changing bonds with their partner, and declining and improving physical and mental health (Deater-Deckard, 2004). However, it is different for parents of children with special needs.

Children with special needs require special handling due to developmental disorders and abnormalities experienced by children (Desiningrum, 2016). Children with special needs show developmental differences compared to children of the same age (Faradina, 2016). Children with special needs or children with disabilities can place additional burdens on parents, including financial, physical, and emotional demands. Previous research has shown that parents of children with special needs experience higher levels of stress and depression than other parents, and disruption of the family unit (Benson & Karlof, 2009).

Parents who have children with special needs are very likely to experience difficulties in managing stress. The stress experienced by parents tends to be caused by their children's behavior (Lestari, Nursalam, & Nastiti, 2021). The pressure experienced by parents with children with special needs can also trigger parental burnout. Parental burnout is not ordinary parenting stress (Brianda et al, 2020). Parental burnout is defined as a state of intense exhaustion related to the caregiving role, where a person emotionally doubts their ability to be a good parent (Roskam, Raes, & Mikolajczak, 2017). The impact of parental burnout on parents is a serious condition with severe consequences for parents (e.g. suicidal ideation) (Brianda, et al., 2020).

A study conducted on parents of neonates with hyperbilirubinemia showed that there was a significant influence between parenting stress and burnout (Vinayak & Dhanoa, 2017). Parents who experience pressure in parenting, both physical and emotional, are called parenting stress (Lauer & Lauer, 2023). According to Abidin (Ahern, 2004), parenting stress is excessive anxiety or tension experienced by parents towards their role as parents and interactions with their children. In his research, Abidin (1992) found that high levels of parenting stress will lead to increased parenting dysfunction. The phenomenon of parenting stress that occurs in parents with children with special needs is caused by the chronic condition of the child's disability both clinically and emotionally. This makes parents demand and feel responsible for parenting that exceeds their abilities, making it difficult for parents to play a parental role (Shaffer, 2012).

To reduce the anxiety and pressure felt by parents in parenting, parents must know the factors that affect parenting stress. Abidin (1992) revealed that three main factors influence parenting stress, namely: child characteristics, parent characteristics, and environmental characteristics. Child characteristics include the child's lack of adaptation, the child's demands on parents, and the child's hyperactive mood and behavior. Parent characteristics consist of the level of depression, parental role, and parental health, relationship with spouse, resilient parents, and social support. Environmental characteristics consist of parent and child attachment, and conformity of parental expectations for children. The focus of this research is how resilience and social support influence parental burnout and parental stress.

Previous research suggests that cultivating and maintaining resilience is a psychological burnout prevention strategy (Harker, Pidgeon, Klaassen, & King, 2016). A recent study on parental burnout in Chinese mothers showed similar findings compared to parents with low resilience, parents with higher resilience felt lower levels of parental burnout (Chen, Liu, & Guo, 2022). Resilient parents can also adapt to their children's disorders and show behavior that accepts the child's condition (Valentia, Sani, & Guo, 2022). In general, resilience is considered an important psychological factor that leads to relatively stable personality characteristics and allows individuals to adapt to various obstacles and barriers. (Sarkar & Fletcher, 2014).

Preventing burnout and stress felt by parents of children with special needs requires not only strengthening through internal factors but also strengthening from external factors. Raikes & Thompson (2005), in their research entitled self-efficacy and social support as predictors of parenting stress among families in poverty, showed that social support has a significant relationship with parenting stress. This research is corroborated by Boyd's research (Bonis, 2016) which reveals that parents who get social support will experience low parenting stress and have a more positive relationship with their children. Conversely, if parents do not get social support, then parents will have difficulty dealing with their children. Social support is a coping mechanism that is believed to help parents overcome the difficulties experienced when raising children with disabilities (Theule, 2010). The social support that parents receive will be a motivation to provide better parenting even though parents experience stress (Thompson & Raikes, 2005). This research examines whether resilience and social support can provide a buffering effect on the stress felt by parents to reduce the impact of parental burnout on parents who have children with special needs.

Research Methods

The method to be used in this research is a quantitative approach, by testing the hypotheses that have been prepared. Quantitive research is widely required to use numbers, starting from data collection, interpretation of the lift, and appearance of the results (Arikunto, 2012). The research design used in this study is causality research. Causality research design is research conducted to determine the effect between one or more variables on certain variables (Ariwidanta, 2016).

The population in this study was parents of children with needs who live in Karawang City, West Java Province, Indonesia. The sampling technique in this study used purposive sampling. Determination of the number of samples in this study using the Lemeshow’s formula, because the population is unknown, so the minimum number of samples needed is 288 respondents. The respondents obtained in this study were 334 parents of children with special needs.

The variables examined in this study are parental stress, and parental burnout with resilience, and social support as moderators. Measurement of parental burnout variables using measuring instruments Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA) short version. This scale is used based on aspects of burnout according to Roskam et al, (2017) the scale consists of 12 items, namely emotional exhaustion consisting of physical fatigue and emotional fatigue, mental distance, cognitive impairment, and emotional impairment. The parental burnout scale developed by Roskam et al, (2017), has been deemed valid and reliable with reliability tests ranging from 0.89 to 0.94 (Roskam., 2017). The measuring instrument used to measure parenting stress in this study is the Parental Stress Scale (PSS) compiled by Berry and Jones (1995) and adapted from previous researchers Kumalasari et al, (2022) based on a self-report developed from Berry & Jones' (1995) Parenting Stress Scale (PSS) measuring instrument, which consists of 15 items with Cronbach's Alpha 0.828.

The measurement of resilience in this study is based on the Chinese version of the resilience scale designed by Yu and Zhang (2007), the scale is an adaptation of Connor- Davidson's Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Yu and Zhang (2007) presented a resilience scale totaling 25 items in the form of statements. Measurement of social support variables using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) measuring instrument from Laksmita, Chung, Liao, & Chang, (2020) based on the theory of Zimet, Tonsing, & Tse, (2012), which consists of 12 items with Cronbach's Alpha 0.81. Social support is divided into three subscales or aspects, namely family, friends, and significant others.

Research Results and Discussion

Research Results

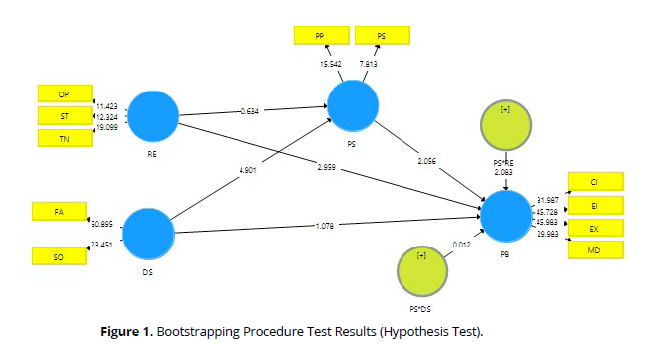

Research data analysis using the Structural Equation Model (SEM) using Smart PLS version 3.0, consisting of three stages, namely Outer Model Analysis (Measurement Model), Inner Model Analysis (Structural Model), and hypothesis testing. The measurement model (outer model) is used to assess the validity of the model. The validity test is conducted to determine the ability of the research instrument to measure what should be measured (Abdillah, 2009) (Table 1).

| Variables | Indicator | Outer Loading |

AVE | Cronbach's Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EX | 0.905 | |||

| Parental Burnout | MD | 0.864 | 0.782 | 0.935 |

| CI | 0.880 | |||

| EI | 0.888 | |||

| Parental Stress |

PP | 0.871 | 0.684 | 0.812 |

| PS | 0.781 | |||

| TN | 0.855 | |||

| Resilience | ST | 0.897 | 0.747 | 0.898 |

| OP | 0.839 | |||

| FA | 0.932 | 0.899 | 0.899 | |

| Social Support | SO | 0.874 | ||

| PS*RE | 1.040 | 1.000 | - |

Based on the results of the outer model analysis, it is found that the measurements of validity through the measurement of outer loading that not all items that have indicators are declared valid. The social support variable with the FR or friends indicator is declared invalid because it has a loading factor value below 0.7, which is 0.650. For this reason, it is necessary to test the validity of the second model again by not re-including the previous invalid item. The results of the second model retest can be seen in Table 1 above. The results of re-estimating the loading factor, have met the standard value of convergent validity, all indicators meet the criteria by having a factor loading value >0.7. Furthermore, in testing the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) value, which is >0.5, so it can be said that all constructs are valid and can be used to measure each latent variable.

Furthermore, reliability testing using Cronbach's Alpha has a value above 0.7. Therefore, it can be concluded that the variables tested are reliable so that structural model or inner model testing can be carried out. Structural model analysis by testing the inner structural model is carried out to see the effect of the relationship between constructs, the significance value, and the R-square of the research model. The structural model is evaluated using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), R-square, and Predictive Relevance (Q2) (Table 2).

| Variable | VIF | R Square Adjusted | Predictive Relevance (Q2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Burnout | Parental Stress | |||

| Parental Burnout | 0.057 | 0.047 | ||

| Parental Stress | 1.132 | 0.090 | 0.056 | |

| Resilience | 1.007 | 1.005 | ||

| Social Support | 1.124 | 1.005 | ||

| PS*RE | 1.026 | |||

Based on the results of the inner model analysis using the collinearity test. Collinearity is a term to describe a correlation between latent variables in the model. The first collinearity result can be seen through the correlation value between observed variables (VIF). Indicators of inner model collinearity occur if the VIF value >7 then the constructed variable must be removed from the structural model (unfit model). Table 2 shows that the VIF value for all variable constructs is below 7, and it can be concluded that there is no multicollinearity between independent variables.

Furthermore, the results of the adjusted R-Square value (R2) or the coefficient of determination of the exogenous constructs simultaneously affect parental burnout by 0.057 or 5.7%. In other words, the parental burnout variable is influenced by the variables in the model by 5.7%, namely parental stress, resilience, and social support. The remaining 94.3% is influenced by other factors outside the model. Furthermore, the adjusted R-square value (R2) or the coefficient of determination of the parental stress variable is 0.090 or 9%. In other words, the parental stress variable is influenced by the variables in the model by 9%, namely resilience, and social support. The remaining 91% is influenced by other factors outside the model. Furthermore, in obtaining the results of predictive relevance (Q2), the results of parental burnout and parental stress are 0.047 and 0.056. This value is greater than 0, which means that a construct model is relevant. This means that the exogenous variables used to predict endogenous variables are quite appropriate (Table 3, 4 & Figure 1).

| Original Sample (O) |

Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | Criteria | P Values | Criteria | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Stress -> Parental Burnout | 0.134 | 0.062 | 2.160 | T-statistik >1.96 | 0.031 | P Value <0.05 |

| Resilience -> Parental Burnout | -0.196 | 0.059 | 3.349 | 0.001 | ||

| Social Support-> Parental Burnout | 0.062 | 0.064 | 0.963 | 0.336 | ||

| Resilience -> Parental Stress | 0.035 | 0.061 | 0.578 | 0.563 | ||

| Social Support -> Parental Stress | -0.304 | 0.066 | 4.618 | 0.000 | ||

| Original Sample (O) |

Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | Criteria | P Values | Criteria | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS->PS*PB | -0.041 | 0.020 | 2.071 | T-statistik >1.96 | 0.039 | P value <0.05 |

| RE->PS*PB | -0.005 | 0.010 | 0.493 | 0.622 |

The results of testing the direct effect hypothesis showed that the effect of parental stress on parental burnout showed a p-value of 0.031 (<0.05), so it can be concluded that the hypothesis is accepted. Further findings found that the effect of resilience on parental burnout showed a p-value of 0.001 (<0.05), so it can be concluded that the hypothesis is accepted. The effect of social support on parental burnout shows a p-value of 0.336 (<0.05), so it can be concluded that the hypothesis is rejected. The effect of resilience on parental stress in parents of children with special needs shows a p-value of 0.563 (<0.05), so it can be concluded that the hypothesis is rejected. The effect of social support on parental stress in parents of children with special needs in Karawang shows a p-value of 0.000 (<0.05), so it can be concluded that the hypothesis is accepted.

The next research finding is the indirect effect of parental stress on parental burnout through the social support variable in parents of children with special needs, which obtained a p-value of 0.039 (<0.05), where this value indicates a moderating influence, so it can be concluded that the hypothesis is accepted. Based on these results, it can be interpreted that social support can function as a moderator of the influence of parental stress on parental burnout in parents of children with special needs. It can be concluded that social support can reduce the influence of parental stress on parental burnout in parents of children with special needs.

The results of the next indirect effect hypothesis are the effect of parental stress on parental burnout with resilience as a moderator on parents of children with special, showing a path coefficient value of -0.005, a T-Statistic value of 0.493 (>1.96), and a p-value of 0.622 (<0.05), where this value indicates a moderating influence, so it can be concluded that the hypothesis is accepted. Based on these results, it can be interpreted that resilience can function as a moderator of the influence of parental stress on parental burnout in parents of children with special needs. It can be concluded that resilience can reduce the influence of parental stress on parental burnout in parents of children with special needs.

Discussion

Parental stress in this study has a direct and significant effect on parental burnout. Similar to research by Liu, et al., (2023) which states that stress in parenting is a risk factor for parental burnout in parents in China who have children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). In a hierarchical regression analysis study conducted by Skjerdingstad, et al., (2022) identifying factors contributing to parental burnout among parents in Norway during the Covid-19 pandemic, it was found that parental stress and the use of unhelpful coping strategies were significantly associated with parental burnout. Furthermore, the findings of the Skjerdingstad, et al., (2022) study found that parental stress measured in the earliest phase during the Covid-19 pandemic was associated with parental burnout 3 months later. Stress felt by parents is a determining factor of parental burnout.

The relationship between parental burnout and parental stress can be noted as the pressure or stress felt by parents of children with disabilities will lead to emotional and physical exhaustion felt by parents. Increased stress on parents will result in chronic imbalances that lead to parental burnout (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018). High levels of stress in parenting can lead to parental burnout, a condition that has consequences for both parents and children. Duygun & Sezgin, (2003) reported that parental burnout occurs when the demands of family needs continue. These persistent demands drain parents' motivation and they may experience emotions of self-blame and anger. Caregiver burnout is the final step in the progression of parental stress, where the experience is no longer healthy for the caregiver and the person receiving care.

Resilience in this study has a direct and significant effect on parental burnout. This is in line with the opinion of Fletcher & Sarkar, (2013) resilience acts as a protective factor to withstand the impact of burnout, thus explaining why some people can survive in difficult situations. In line with the findings of Sorkkila & Aunola (2022) resilience is statistically significantly and negatively related to parental burnout: the higher the level of resilience showed by parents, the lower the level of parental burnout.

A recent study on parental burnout in Chinese mothers showed similar findings. Compared to parents with lower resilience, parents with higher resilience perceived lower levels of parental burnout (Chen, Qu, Yang, & Chen, 2022). Parental resilience is defined as the capacity of parents to provide competent and quality parenting to children despite adverse personal, family, and social conditions (Gavidia-Payne et al., 2015). Having a child with special needs puts pressure on the whole family who experience various psychological stresses related to the child's disability. In general, resilience is considered an important psychological factor that leads to relatively stable personality characteristics and can adapt to various conditions (Fletcher & Sarkar, 2013).

In this study, it was found that social support no significant parental burnout. This is not in line with the research proposed by Gugliandolo et al., (2021) which states that social support is the main resource that contributes to meeting all the basic needs of parents and making parents resilient in the face of obstacles and difficulties. Social support refers to individuals' perceptions of their potential access to support from their social networks (Uchino in Williams, Morelli, Ong, & Zaki, 2018). As seeking social support is one of the ways parents cope with parenting stresses (Masarik & Conger, 2017), it is not surprising that previous research has cited perceived social support as a strong protective factor against parental burnout (Yamoah, 2021).

Although social support is generally viewed as positive, lack of social support does not cause parental burnout in all parents. According to the risk-resource balance theory of parental burnout (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018), this may be because the absence of one important resource (e.g., social support) can be compensated for by the presence of other resources that have equal or higher weight. Perceived social support may also lead to maladaptive out come or may not be effective in achieving well-being in some cases (Rohde-Brown & Rudestam, 2011). This is supported by research by Prins, et al., (2015) which states that there is no significant relationship between social support and burnout; this may indicate that the social support received does not affect the burnout felt by individuals.

Furthermore, this study also found that resilience has no significant parental stress in parents of children with special needs. The findings of this study are not in line with the results of research conducted by Llauradó & Riveiro, (2020) defining the relationship between parental stress and resilience as a significant and negative relationship, and considering the relationship as a protective factor against stress. Supporting these findings, Suzuki et al. (2018) stated that family resilience reduces maternal stress, just as the resilience capacity in the family affects individual resilience. The relationship between parental stress and resilience has been widely researched, parents with children who have neurodevelopmental disorders experience high stress and low resilience compared to parents who do not have children with neurodevelopmental disorders (Cara García in Andrés-Romero et al., 2021). Correspondingly, it has been shown that parents of children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) have significantly lower resilience than parents of children with normal/typical development (Tijeras Iborra, in Andrés-Romero et al., 2021).

However, not all families experience the same stress, as their approach to parenting may differ, and the personal characteristics of parents and children, the family climate, and the socio-economic circumstances of the family may be different. (Hayes & Watson, 2013) all greatly influence the condition of parents (Oronoz, Alonso-Arbiol, & Balluerka, 2007) and their perceptions of their abilities and confidence as parents (Aracena, et al. (Aracena, et al., 2016). This may help to explain the relevant dynamics regarding the non-effect of buffering resilience to reduce parental stress in parents of children with special needs. So that the presence or absence of reinforcement through resilience, will not affect the parental stress felt by parents of children with special needs.

The results of further research found that social support has an influence on parental stress in parents of children with special needs in Karawang City, West Java Province, Indonesia. In line with what was conveyed (Arika et al., 2019) in a study stating that social support is an important source for parents who experience stress due to children's behavior. Social support is broadly defined as social connections or resources provided by others to help someone cope with stressful or difficult circumstances (Cohen & Wills in Schellinger, et al., 2020). Furthermore, other studies have also found that social support is beneficial for mothers who experience increased parenting demands in early childhood (Arikan et al., 2019) or stress in parenting children with challenging behaviors (Cherry, Gerstein, & Gerstein, 2019). Therefore, social support may serve as an important family resource that buffers the effects of stress on parents.

Social support provided by the social environment appears to be an important element in the social dynamics of respondents as lack of support is associated with clinical stress (Lima, Cardoso, & Silva, 2016). Furthermore, in Glenn et al.'s (2009) research findings, low social support receipt, and poor family cohesion were shown to favor higher levels of parental stress in mothers. Children's intellectual, emotional, and behavioral problems further add to the caregiver's burden and can negatively impact the quality of life and health of parents (Carona et al, 2013). Carona et al. (2013) studied parents of children with and without Cerebral Palsy and concluded that the increased burden of caregiving appears to lead to negative perceptions of social support, which in turn impairs parents' psychological adjustment.

The results of further research found that social support can act as a moderator of the influence of parental stress on parental burnout. This is in line with the research of Zhao et al, (2023) who found that support plays a role as a moderator between parental stress and parental burnout if parents who obtain high social support can effectively reduce the impact of stress in parenting on burnout felt by parents. Higher social support can directly lead to higher life satisfaction and lower burnout (Mahmoud, Staten, Lennie, & Hall, 2015). Whether one is under stress or not, social support can maintain good emotional experiences and benefit mental health. (Li, 1998).

Social support is one of the protective factors against adverse psychological effects such as stress and burnout. The potential effect of social support is to reduce the impact of stress on burnout. This may alter the relationship between stress and burnout, helping parents of high-stress children with special needs to cope better and only develop moderate levels of burnout. This effect of social support as a moderating variable is particularly important in cases where the direct influence of stress levels or experiences on burnout is not possible.

Furthermore, the findings in this study that resilience cannot act as a moderator of the influence of parental stress on parental burnout. This contradicts the results of Liu, et al.'s (2023) study which found that resilience partially mediates the relationship between parental stress in parenting and burnout of parents who have children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). This study highlights stress in parenting ASD children as a risk factor for parental burnout and resilience is a potential mechanism underlying this relationship. Bitsika, Sharpley, & Bell, (2013) found that moderation analysis showed that psychological resilience acts as a buffer against the development of increased burnout in parents with children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) associated with high levels of daily stress due to parenting. Consideration of the variance in the types of children with special needs, and other services obtained by parents of children with special needs in the treatment and care of children with special needs, can help to explain the relevant dynamics regarding the non-effect of parental stress and resilience as buffering to reduce burnout felt by parents. In addition, 81,44% of respondents have more than 2 children, with an average age of children with special needs above 8 years. This is what is allegedly able to increase the burden of parents of children with special needs in accompanying, caring for, and providing optimal care. Increased stress with the perception that parents have of the lack of resources they have, as well as feelings of lack of optimism towards children with special needs, is what makes resilience less able to play a role in blocking the effects of stress on burnout.

Implications

The findings in this study hope that future research can consider social support as a variable that has an important position in reducing parental burnout. This study may also trigger future research to evaluate the role of social support. Evaluation of the role of social support in terms of mediation or moderation given to individuals, especially about parental burnout, and parental stress. These findings have important value for the social environment, educational institutions, and/or communities of children with special needs, as well as other institutions involved. In the findings of this study, the context of social support involves family support and spousal support, so that efforts to provide social support to parents of children with special needs can be explicitly centered through the support of the closest relatives so that they can deal with the difficulties experienced in providing care and care for children with special needs.

Literature

Abdillah, W., & Jogiyanto, H. (2009). Partial Least Square (PLS) Alternative SEM in Business Research. Yogyakarta: Andi Publisher.

Abidin, R. R. (1992). The determinants of parenting behavior. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, Vol 21, No. 4, 407-412.

Ahern, L. S. (2004). Psychometric Properties of The Parenting Stress Index-Short Form. (Thesis). Raleigh, North Carolina: Faculty of Psychology of North Carolina State University.

Andrés-Romero, M. P., Flujas-Contreras, J. M., Fernández-Torres, M., Gómez-Becerra, I., & Sánchez-López, P. (2021). Analysis of Psychosocial Adjustment in the Family During Confinement: Problems and Habits of Children and Youth and Parental Stress and Resilience. Original Research, 1-18.

Aracena, M., Muzzio, E. A., Undurraga, C., Leiva, L., Chavez, K. M., & Molina, Y. (2016). Validity and Reliability of the Parenting Stress Index Short Form (PSI-SF) Applied to a Chilean Sample. Journal Child and Family Studies Vol. 25 (12).

Arika, G., Kumru, A., Korkut, B., & Ilhan, A. O. (2019). Examining Toddlers Problem Behaviors: The Role of SES, Parenting Stress, Perceived Support, and Negative Intentionality. Journal of Child and Family Studies.

Arikunto, S. (2012). Research Procedure An Approach. Jakarta: Rieneka Cipta.

Ariwidanta, K. T. (2016). The effect of risk on profitability with adequacy as a mediating variable. Journal of Management.

Benson, P. R., & Karlof, K. L. (2009). Anger, stress proliferation, and depressed mood among parents of children with ASD: a longitudinal replication. Journal of Autism Development Disorder, 350-362.

Berry, J. O., & Jones, W. H. (1995). The Parental Stress Scale: Initial psychometric evidence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, Vol. 12, No. 3, 463-472.

Bitsika, V., Sharpley, C. F., & Bell, R. (2013). The Buffering Effect of Resilience on Stress, Anxiety and Depression in Parents of a Child with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, Vol. 25, No. 5, 533-543.

Bitsika, V., Sharpley, C. F., & Bell, R. (2013). The Buffering Effect of Resilience on Stress, Anxiety and Depression in Parents of a Child with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Development Phys Disability.

Bonis, S. (2016). Stress and Parents of Children with Autism: A Review of Literature. Issues in mental health nursing, Vol. 37, No. 3, 153-163.

Brianda, M. E., Roskam, I., Gross, J. J., Franssen, A., Kapala, F., Gérard, F., & Mikolajczak,

M. (2020). Treating Parental Burnout: Impact of Two Treatment Modalities on Burnout Symptoms, Emotions, Hair Cortisol, and Parental Neglect and Violence. Psychother Psychosom.

Brown, S. M., Doom, J. R., Lechuga-Peña, S., Watamura, S. E., & Koppels, T. (2020). Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse & Neglect.

Carona, C., Pereira, M., Moreira, H., Silva, N., & Canavarro, M. C. (2013). The Disability Paradox Revisited: Quality of Life and Family Caregiving in Pediatric Cerebral Palsy. Journal of Child and Family Studies, Vol. 22 (7), 971-986.

Chen, B.-B., Qu, Y., Yang, B., & Chen, X. (2022). Chinese mothers' parental burnout and adolescents' internalizing and externalizing problems: the mediating role of maternal hostility. Dev. Psychol Vol. 58, 768-777.

Chen, M., Liu, X., & Guo, J. (2022). Relationship between social support and parental burnout in COVID-19 among Chinese young parents. Journal of Peking University Health Sciences, Vol. 54, No.3, 520-525.

Cherry, K. E., Gerstein, E. D., & Ciciolla, L. (2019). Parenting Stress and Children's Behavior: Transactional Models During Early Head. Journal of Family Psychology, 1-30.

Deater-Deckard, K. (2004). Parenting Stress. New Haven: Yale University Press. Desiningrum, D. R. (2016). Psychology of Children with Special Needs. Jakarta:

Psychoscience.

Duygun, T., & Sezgin, N. (2003). The effects of stress symptoms, coping styles and perceived social support on burnout levels of mentally handicapped and healthy children's mothers. Türk Psikoloji Dergisi 18(52), 37-55.

Faradina, N. (2016). Self-Acceptance in Parents Who Have Children with Special Needs. Psychoborneo, Vol. 4, No.1, 18-26.

Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2013). Parenting stress and parenting resources (perceived family support, psychological resilience) not only directly affect parental burnout, they also interact. According to JD-R theory, parenting resources can reduce the impact of parenting stress on parenta. Eur Psychol Vol. 18, 12-23.

Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2013). Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. . Eur. Psychol. Vo. 18, 21-23.

Gavidia-Payne, S., Denny, B., Davis, K., Francis, A., & Jackson, M. (2015). Parental resilience: A neglected construct in resilience research. Clinical Psychologist Volume 19 (3), 111-121.

Glenn, S., Cunningham, C., Poole, H., Reeves, D., & Weindling, M. (2009). Maternal parenting stress and its correlates in families with a young child with cerebral palsy. Child: care, health and development, Vol. 35 (1), 71-78.

Gugliandolo, M. C., Cuzzocrea, F., Costa, S., Soenens, B., & Liga, F. (2021). Social support and motivation for parenthood as resources against prenatal parental distress. Social Development Vol. 30, 1131-1151.

Harker, R., Pidgeon, A. M., Klaassen, F., & King, S. (2016). Exploring resilience and mindfulness as preventative factors for psychological distress burnout and secondary traumatic stress among human service professionals. Work, Vol. 54, No. 3, 631-637.

Hayes, S. A., & Watson, S. L. (2013). The impact of stress in parenting: a meta-analysis of studies comparing experiences of stress in parenting in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism Developmental Disorders, Vol. 43, No. 3.

Kumalasari, D., Gani, I. A., & Fourianalistyawati, E. (2022). Adaptation and Psychometric Properties of the Indonesian Version of the Parental Stress Scale. Journal of Indigenous Psychology: Indonesian Journal of Indigenous Psychology, Vol. 9, No. 2, 332-353.

Laksmita, O. D., Chung, M.-H., Liao, Y.-M., & Chang, P.-C. (2020). Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support in Indonesian adolescent disaster survivors: A psychometric evaluation. PLoS On, Vol. 15, No. 3.

Lauer, R., & Lauer, J. (2023). Marriage and Family: The Quest for Intimacy, 10th Edition. Boston: McGraw Hill.

Lestari, I., Nursalam, N., & Nastiti, A. A. (2021). Analysis of Factors Affecting Nurse Anxiety During Pandemic Covid-19. Psychiatry Nursing Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1, 15-22.

Li, Q. (1998). Social support and individual mental health. Tianjin Social Science Vol. 1, 66 - 69.

Lima, M. B., Cardoso, V. d., & Silva, S. S. (2016). Parental Stress and Social Support of Caregivers of Children With Cerebral Palsy. Paidéia, Vol. 26 No.64, 207 - 214.

Liu, S., Zhang, L., Yi, J., Liu, S., Li, D., Wu, D., & Yin, H. (2023). The Relationship Between Parenting Stress and Parental Burnout Among Chinese Parents of Children with ASD: A Moderated Mediation Model. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

Liu, S., Zhang, L., Yi, J., Liu, S., Li, D., Wu, D., & Yin, H. (2023). The Relationship Between Parenting Stress and Parental Burnout Among Chinese Parents of Children with ASD: A Moderated Mediation Model. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1- 11.

Llauradó, V., & Riveiro, S. (2020). Resiliencia, satisfacción y situación de las familias con hijos/as con y sin discapacidad como predictores del estrés familiar. Ansiedad Estrés Vol. 26, 59 - 62.

Mahmoud, J. S., Staten, R. T., Lennie, T. A., & Hall, L. A. (2015). The Relationships of Coping, Negative Thinking, Life Satisfaction, Social Support, and Selected Demographics With Anxiety of Young Adult College Students. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 1-15.

Masarik, A. S., & Conger, R. D. (2017). Stress and child development: A review of the Family Stress Model. Current Opinion in Psychology, Vol. 13, 85-90.

Mikolajczak, M., & Roskam, I. (2018). A Theoretical and Clinical Framework for Parental Burnout: The Balance Between Risks and Resources (BR2). Developmental Psychology Vol. 9.

Novrianto, R., Marettih, A. K., & Wahyudi, H. (2019). Construct Validity of the Indonesian Version of the General Self Efficacy Scale Instrument. Journal of Psychology Volume 15 Number 1, June 2019, 1-9.

Oronoz, B., Alonso-Arbiol, I., & Balluerka, N. (2007). A Spanish adaptation of the Parental Stress Scale. Psicothema, Vol.19, Issue. 4.

Prins, J. T., Hoekstra-Weebers, J. E., Gazendam-Donofrio, S. M., Wiel, H. B., Sprangers, F., Jaspers, F. C., & Heijenden, F. M. (2015). The role of social support in burnout among Dutch medical residents. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 12(1), 1-6.

Raikes, H. A., & Thompson, R. A. (2005). Efficacy and Social Support as Predictors of Parenting Stress Among Families in Poverty. Infant Mental Health Journal, Vol. 26, No. 3, 177-190.

Rohde-Brown, J., & Rudestam, K. E. (2011). The Role of Forgiveness in Divorce Adjustment and the Impact of Affect. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 109-124.

Roskam, I., Raes, M.-E., & Mikolajczak, M. (2017). Exhausted Parents: Development and Preliminary Validation of the Parental Burnout Inventory. Front Psychology, Vol.8.

Sarkar, M., & Fletcher, D. (2014). Psychological resilience in sport performers: a review of stressors and protective factors. Journal of Sports Sciences, 1419-1434.

Schellinger, K. B., Murphy, L. E., Rajagopalan, S., Jones, T., Hudock, R. L., Graff, J. C., Tylavsky, F. A. (2020). Toddler Externalizing Behavior, Social Support, and Parenting Stress: Examining a Moderator Model. Family Relations: Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Science Vol. 69, 714-726.

Shaffer, C. M. (2012). Parenting stress in mothers of preschool children recently diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. New Jersey: Rutgers University Community Repository: The State University of New Jersey.

Skjerdingstad, N., Johnson, M. S., Johnson, S. U., Hoffart, A., & Ebrahimi, O. V. (2022).

Parental burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. Family Process, 1715-1729.

Sorkkila, M., & Aunola, K. (2022). Resilience and Parental Burnout Among Finnish Parents During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Variable and Person-Oriented Approaches. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families Vol. 30 (2), 139- 147.

Suzuki, K., Hiratani, M., Mizukoshi, N., Hayashi, T., & Inagaki, M. (2018). Family resilience elements alleviate the relationship between maternal psychological distress and the severity of children's developmental disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, Vol. 83, 91 - 98.

Theule, J. (2010). Predicting Parenting Stress in Families of Children With ADHD. Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto.

Valentia, S., Sani, R., & Anggraeny, Y. (2017). The relationship between resilience and parental acceptance among mothers of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Journal of Ulayat Psychology, Vol. 4, No. 1, 43-57.

Vinayak, S., & Dhanoa, S. K. (2017). Relationship of Parental Burnout with Parental Stress and Personality among Parents of Neonates with Hyperbilirubinemia. Indian Psychology.

Williams, W. C., Morelli, S. A., Ong, D. C., & Zaki, J. (2018). Understanding the Links Between interpersonal emotion regulation: Implications for affiliation, perceived support, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 115, Issue. 2, 224-254.

Yamoah, J. (2021). The Role of Social Support in Mitigating Parental Burnout for Mothers of Children with Medical Complexity. Doctor of Education Vol. 81.

Yu, X., & Zhang, J. (2007). Factor analysis and psychometric evaluation of the Connor- Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) in Chinese people. Social Behavior and Personality, 19-30.

Zhao, J., Hu, H., Zhao, S., Li, W., & Lipowska, M. (2023). Parental burnout of parents of primary school students: an analysis from the perspective of job demands-resources. Frontiers in Psychiatry Vol.14.

Zimet, G. D., Tonsing, K., & Tse, S. (2012). Assessing social support among South Asians: The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 5, Issue. 2, 164-168.